The Contract Tracing Race

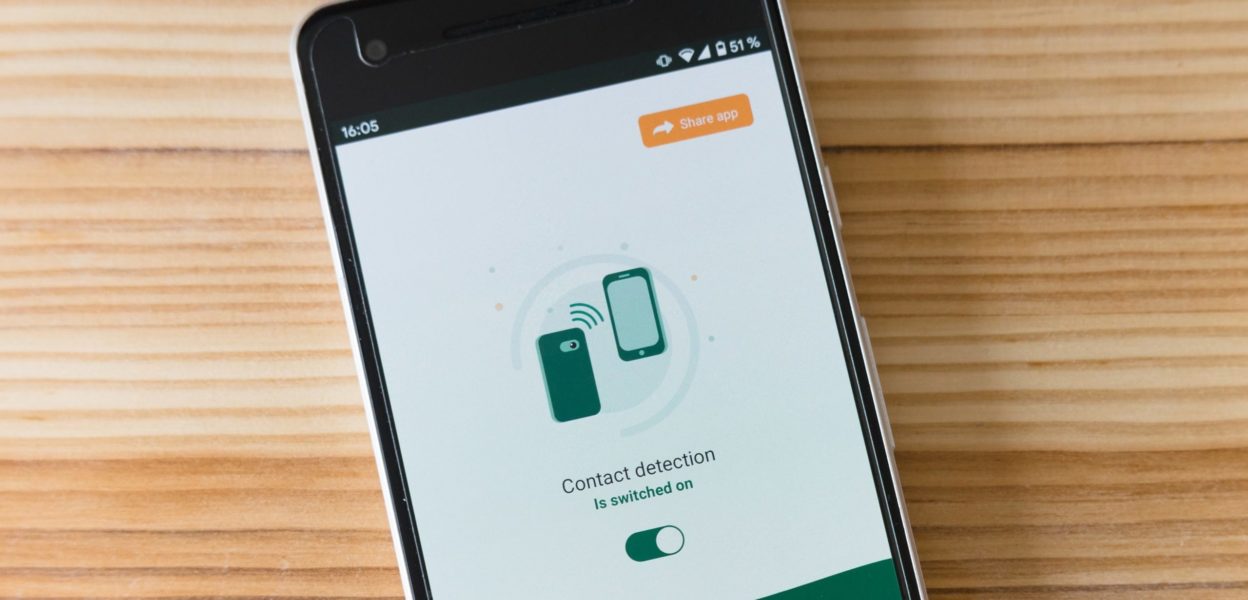

Contact tracing technology acts as a kind of digital handshake in the form of an app, using Bluetooth signals to exchange an anonymous ID when two users come into close proximity. If and when a person using the app reports having flu-like symptoms, the person is asked a series of questions to help determine if COVID-19 is likely and if they need to self-isolate and get tested. The app digitally retraces the person’s steps and alerts others whom they may have infected.

Rewards v. risks

At the time of writing, the UK was tracing COVID-19 infections manually while trialing an app expected to launch nationwide in June. In our urgency to roll out contact tracing technology – and our desire for the freedoms hinging on its success – are we overlooking potential shortcomings? Assessing our risks can help us manage them.

For one, it will likely take time to realise the app’s benefits. Contact tracing requires a broad swath of the population to not only have a smartphone but also download and use the app – Oxford University research suggests 60 percent uptake of the app is a likely estimate. While the UK government has recruited nearly 18,000 human contact tracers to support the contact tracing programme, some members of Parliament have expressed doubt that this number is sufficient to effectively identify and isolate the virus. Contact tracing recruits also reported problems with the organisation and delivery of tracing programme training.

Further, the app may give users a false sense of security – and generate false positives. Registering contacts requires a Bluetooth signal, and a phone may not emit that signal if it is locked or a user isn’t looking at the app. In addition, the range of a Bluetooth device can fluctuate based on how the user holds it, or if the person is indoors or outdoors. A Bluetooth signal can travel through walls, so it may report that a next-door neighbour is a contact even if no contact occurred. This over-reporting of contacts happened during recent trials of the UK’s contact tracing app on the Isle of Wight: Along a street where individuals lived next door to NHS staff or care workers, “cascades of contacts” were registered.

Finally, the sharing and storage of personal data – even anonymised data – sparks privacy concerns. NHSX, the technology arm of the National Health Service and the developer of the app planned for the UK, is using a central computer system to collect reports of COVID-19 symptoms and alert the contacts registered in an infected person’s phone. (Alternatively, an analogous contact tracing app interface developed by Apple and Google is decentralised, with potentially infected contacts matched up via their devices versus through a central database.) Centralised systems are more easily hacked – and while NHSX said it will protect the anonymity of users and that data will only be used for NHS care and research, 2019 research by the University of Louvain and Imperial College found that anonymising personal information isn’t sufficient to protect privacy.

While some of these risks are beyond an individual’s or an organisation’s control, others – such as privacy and cybersecurity risks – can and should be contained. At a time when new threats are surfacing on a regular basis, ongoing risk management can help.

“Increasingly, organisations need to be mindful of how personal data is being collected, stored and shared, as well as where vulnerabilities exist – particularly at a time when large numbers of employees use their smartphone for work,” said Alex Smith, Regional Underwriting Lead for Technology at Travelers Europe. “It’s important to have a thorough risk management plan that includes not only robust cybersecurity protection and employee training but also post-breach support.”

The Knowledge Newsletter

Subscribe to The Knowledge for a no-nonsense view into the latest research and trends before it makes its way to our blog.

We will only use your email address to send you this newsletter. You can unsubscribe at any time. Privacy Policy